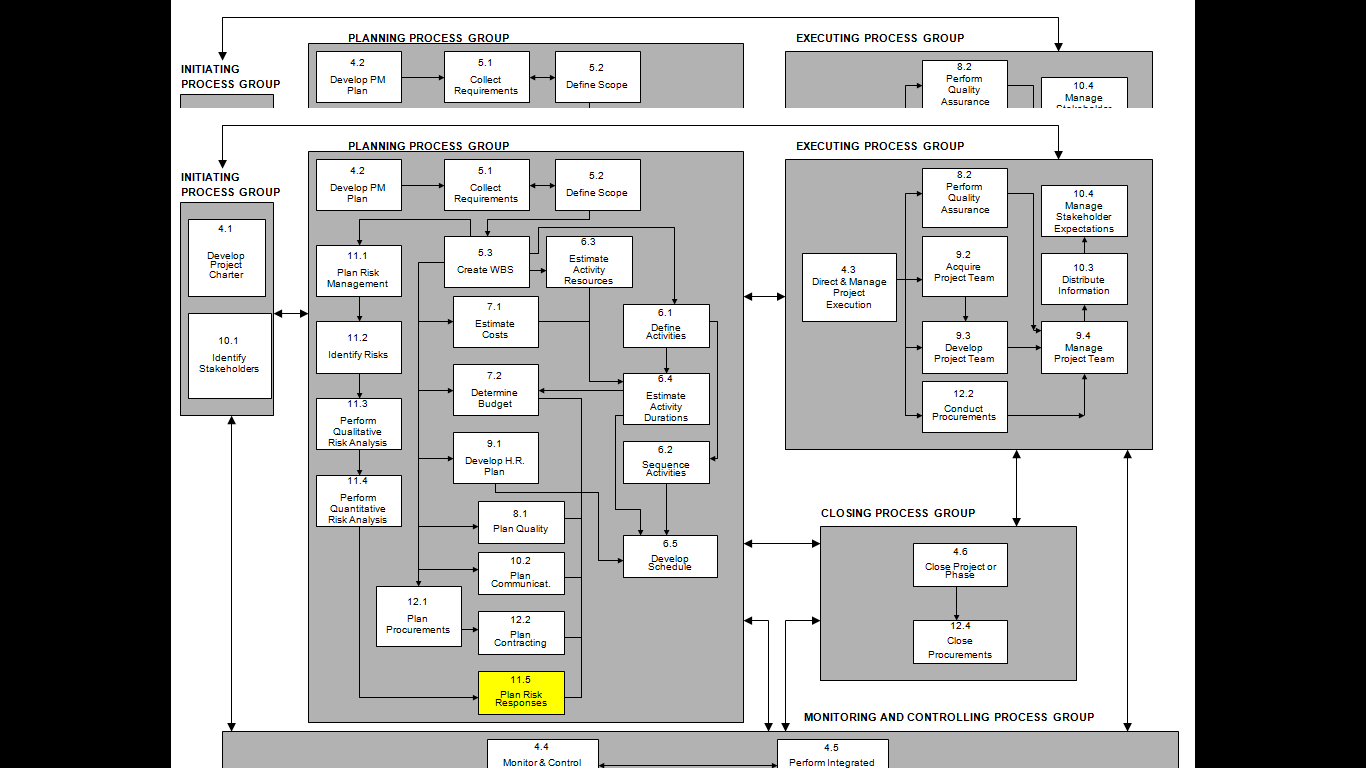

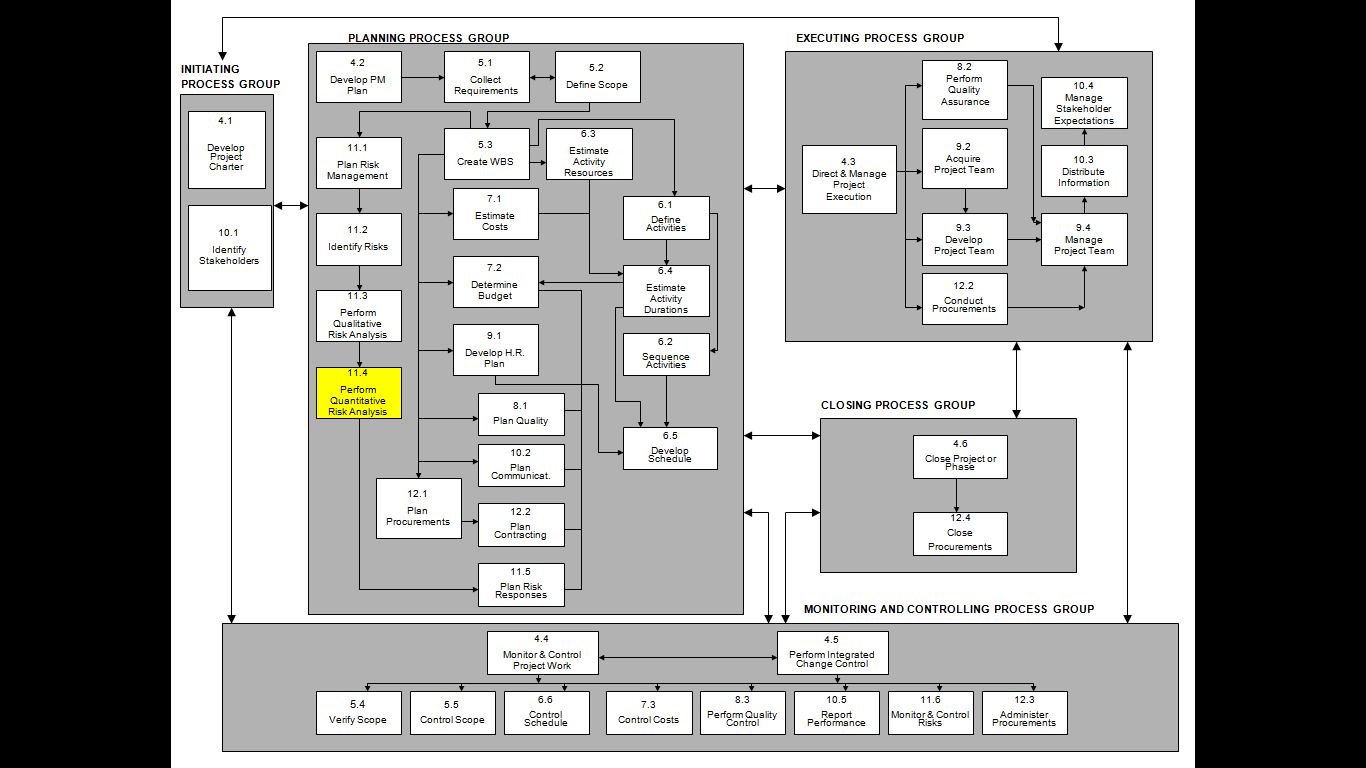

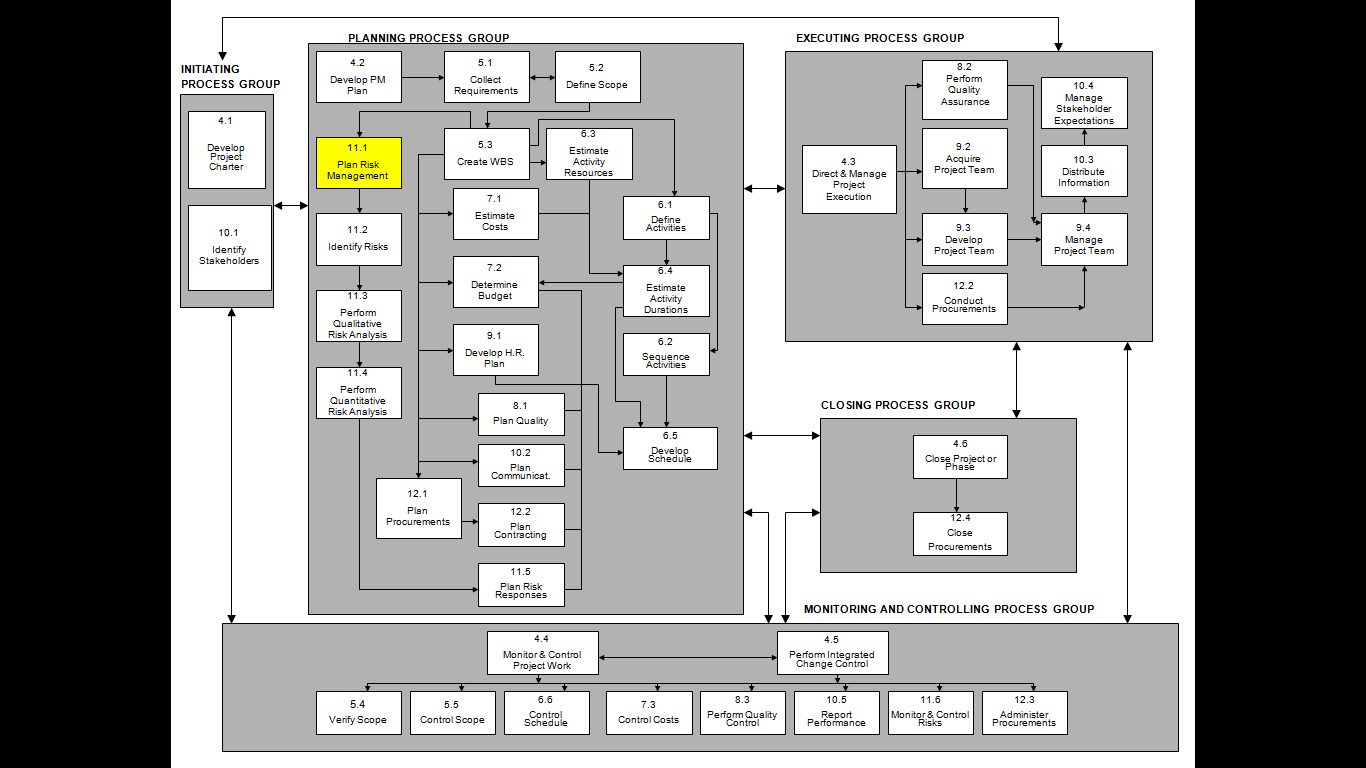

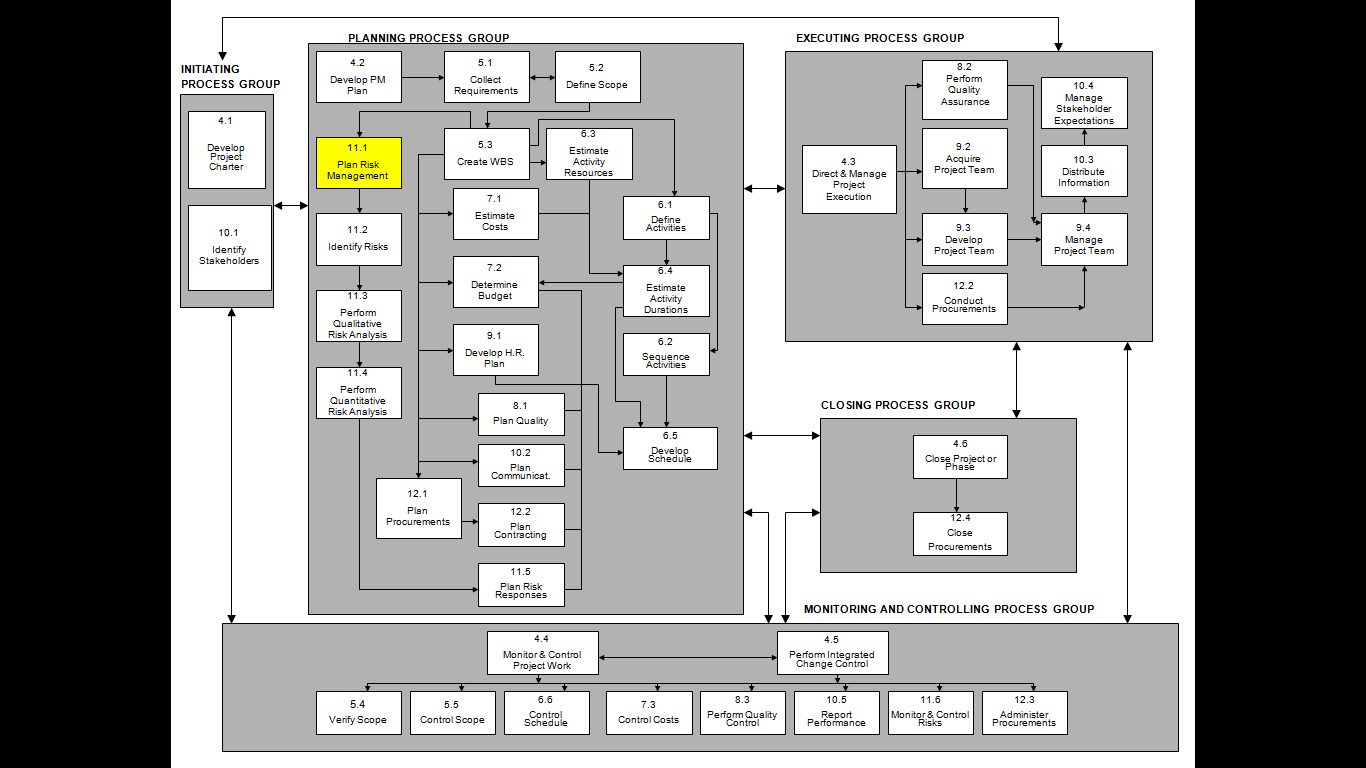

With excerpts from my Project Management Novel, I will illustrate the many processes of the PMBOK. Here is the eighteenth one: Plan Risk Management. Use this map to see how this process fits into the scheme of processes.

After supper, when the younger boys had gone to bed, Gwilym, Fred and Bleddyn discussed Abbot Crawford’s concerns. “He wants us to plan for the risks that might hit the project. Have you any ideas, Fred?”

“We’ve already planned other things: Scope, budget, communications. Why don’t we plan risks th’same way?”

“Right, Fred. So what do we do? First we must come up with a list of risks that could affect our project; all the things that could go wrong. We’ll call that ‘Identify Risks’. Then we need to sort these risks into those that are serious and those that aren’t. How will we do that?”

“There are risks that will cause disaster to th’project if they come to pass. Those are th’risks that we need to worry about.”

“Aye, but what if they are extremely unlikely. Need we spend a lot of time and money trying to stop them from happening when they will likely never happen on their own?”

“I see thy point, Gwilym. But we also don’t need to spend much time worrying about th’risks that are likely but cause not much harm if they happen. Th’risks we have to worry about are those that are likely and dangerous at th’same time.”

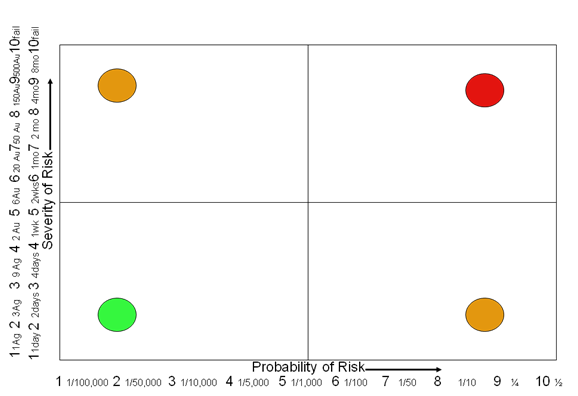

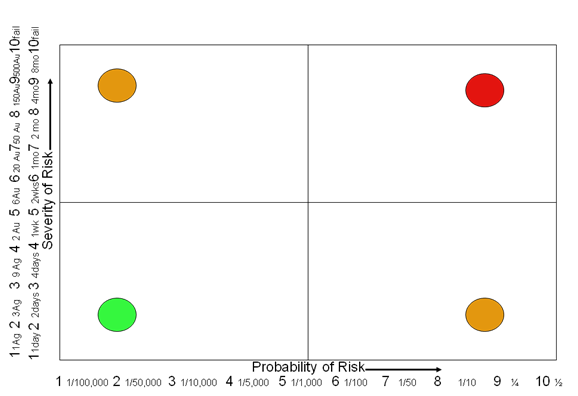

Bleddyn stood up and cleared the dinner board of their drinking mugs. Then he placed a piece of blank parchment and some quills and ink on the board and sat back down, resting it back on his knees and the others. He drew a box intersected by a pair of perpendicular lines, to use as a graph. “I’m labeling the vertical axis: ‘Intensity of Risk’ and the horizontal axis: ‘Probability of risk’. Any risk that is low in probability and intensity, can be ignored.” He placed a dot in the lower left quadrant of the graph.

“Can we change the name of the vertical axis to ‘Severity of Risk’? That sounds better to me,” asked Gwilym.

“Yes, Da. Now, the risks that have high inten…I mean severity and high probability,” he placed a dot in the upper right quadrant, “must be dealt with immediately.”

“That’s right!” exclaimed Fred.

“Now, what about risks in these quadrants?” asked Bleddyn as he drew dots in the upper left and lower right quadrants.

“That’s the question isn’t it?” said Gwilym. They all thought for a while.

Fred spoke up. “What if we gave numbers to th’risks? Rather than just put them in quadrants, add numbers on these axes like this.” He drew numbers from 1 – 10 on both axes. “Then we multiply th’risk times th’severity and we get a number. Th’bigger th’number, th’more seriously we take it.”

Gwilym looked at Bleddyn and both nodded their heads in agreement. Then Bleddyn spoke up. “But how do we measure probability? What is the likelihood of something bad happening? And how do we give that a number from 1 – 10?”

Gwilym pulled on his lower lip. “We need a scale. Something like this.” He turned the parchment so that it was facing him and drew numbers next to Fred’s 1 – 10. Next to the number One, he wrote 1/100,000. Next to the number Ten, he wrote ½. “The chances of something happening needs to be somewhere between these two extremes. Perhaps a Two is 1/50,000. A Nine is ¼. A Three is 1/10,000. An Eight is 1/10.”

Fred squirmed and interrupted, “I get it. A Four is 1/5,000. A Seven is 1/50. A Five is 1/1,000 and a Six is 1/100. Somethin’ like that, right?”

Gwilym had been writing the numbers down that Fred had suggested. “Yes. That is our probability scale. Now we won’t be able to measure exactly what the probabilities are for any risk, but a group of people should be able to come to a consensus whether the likelihood is 1/10,000 or 1/100. Don’t you agree?”

They nodded.

“Now what kind of scale should we use for severity?” asked Bleddyn.

“The project being delayed is the biggest cause of concern. So we should use the scale as number of days of delay the risk causes to the project. So, One means one day delay, Ten means the project fails completely and the numbers in between mean increasingly greater delays.”

Bleddyn had been filling in numbers on the vertical axis.

- One day

- Two days

- Four days

- One week

- Two weeks

- One month

- Two months

- Four months

- Eight months

- Project fails

Gwilym smiled at his son. “I like it; you’ve doubled the previous number each time.”

Fred was frowning. “But what about cost? Some risks don’t affect th’schedule of th’project but still cost money. How will we take care of those risks?”

“I know! Use the same scale but start the costs at one silver and keep doubling it up the scale.”

Bleddyn nodded and wrote next to the previous schedule scale the following:

- One silver

- Two silver

- Four silver

- Ten silver

- One Gold

- Two Gold

- Four Gold

- Eight Gold

- Sixteen Gold

- Thirty-two Gold

“No,” said Gwilym. The upper end is not severe enough. 32 gold is pretty bad but not equivalent to the project failing. Try tripling the cost each unit.”

Bleddyn changed some numbers:

- One silver

- Three silver

- Nine silver

- Two Gold

- Six Gold

- Twenty Gold

- 50 Gold

- 150 Gold

- 500 Gold

- Project Fails

“Much better,” said Gwilym. “Two gold is equivalent to a week delay in the project. And eight months delay is equivalent to about 500 gold in cost. I like it!”

“Aye, but what about if a risk causes an extra cost of one week plus two gold? Then what number do we give it? ‘Tis rarely one or th’other”

“Move to the next highest number. Make that a severity of Five,” suggested Gwilym. They all nodded heads.

“All right then,” said Gwilym. We have the tool we need to sort the risks we identified, what do we call it?”

“Quantify Risks?” suggested Bleddyn. “We end up with a number that indicates how bad the risks are.”

“We do,” agreed Gwilym, “but the number isn’t really the quantity. For instance, if we found a risk that Fred just mentioned that cost a week and two gold and the probability score we gave it was Five, we would score it a Twenty-five. But twenty-five what? Gold? Silver? Days? Twenty-five is not the quantity of the risk. The real risk to the project would be the impact on the cost and the schedule divided by 1,000 because that is the chance of that risk occurring. So the quantified risk would be 1/500 of a gold or one third of a copper piece and 10 minutes. But that’s assuming we know exactly the probability and the severity. More likely we’re just guessing the relative size of the risks.”

“So what we are really doing is performing Risk Qualification, not Quantification. We get a relative number we can use to sort risks into those we have to deal with and those we can allow to happen.”

Fred spoke up. “Do we need th’graph. Can’t we just use th’numbers and th’multiplied result to figure out which risks are worst?”

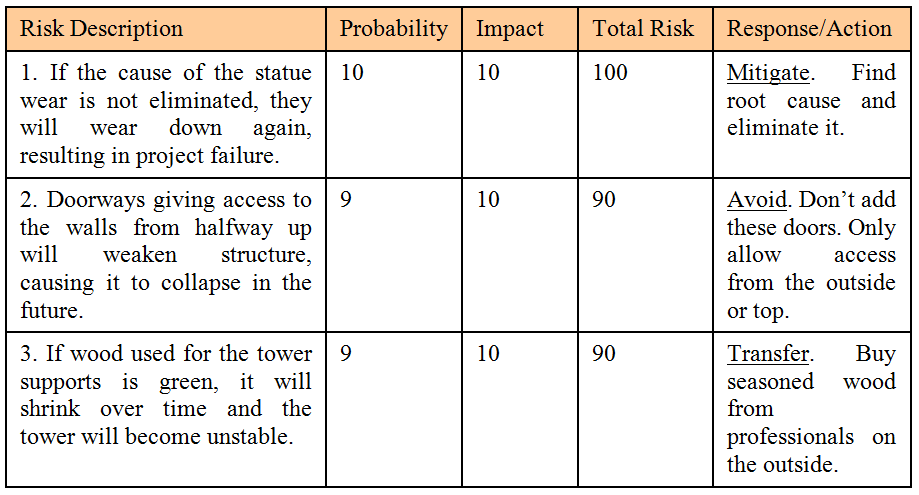

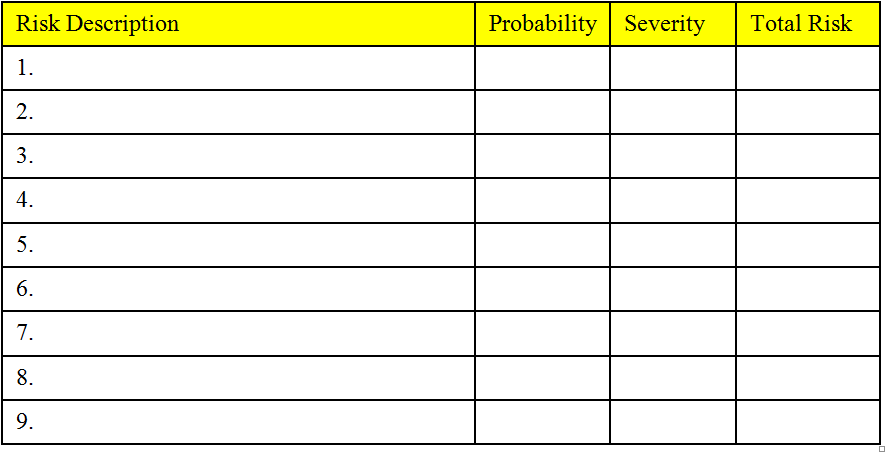

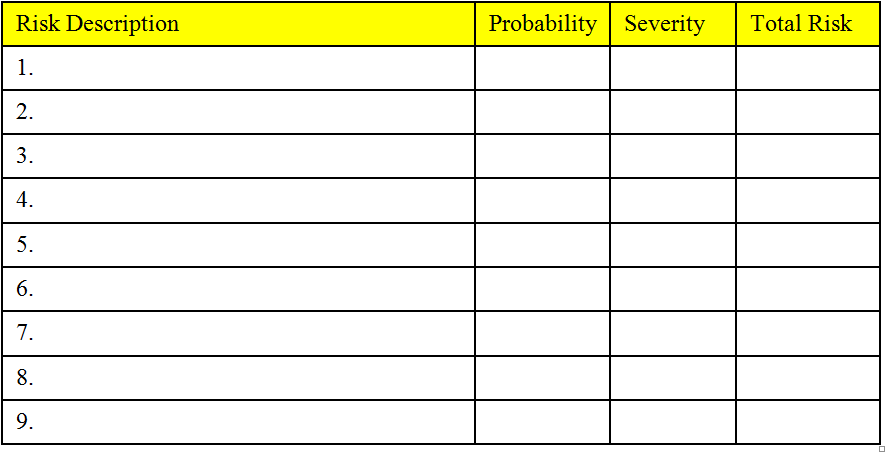

Gwilym realized Fred was correct and he turned the parchment over. “We can use a table instead.” He drew rows and columns. He headed the first column: ‘Risk’, the second: ‘Probability’, the third: ‘Severity’, the fourth: ‘Total Risk’. “Now we can just enter the risks, figure out the numbers using the scales, multiply them together and figure out which risk is the worst.”

“Then what?” asked Bleddyn.

“Then what?” asked Bleddyn.

“Then we need to do something about the bad risks. We need to eliminate them, starting with the worst ones and working our way down.”

“Aye, Bleddyn. But how do tha eliminate risks? In Londinium, we knew that some of th’boat owners might want to get out into th’river after we had blocked it off. But how do you stop that from happenin’?”

“We told the boat owners we ran into that we planned on placing supports for the arch during October and November. We asked them to tell their friends. I suppose we should have made an effort to tell every boat owner our plans so that that one captain wouldn’t have needed to move when it was too late.”

“Would that have eliminated the risk, Da?”

Gwilym thought for a while. “No, son. It wouldn’t have eliminated it. It would have lowered the probability, left the severity the same but wouldn’t have eliminated it.”

“How do tha eliminate a risk?” asked Fred.

“The only way you eliminate a risk entirely is to change the project so that risk cannot happen. In the case of the boats in Londinium, we would have had to make arch supports that still allowed boats to pass underneath.”

“But that’s not possible. Tha would have to build an arch under th’arch for that. Even then, th’boats could not have fit under.”

“That’s right, Fred. Therefore, not all risks can be eliminated. So it is a different strategy. Changing the scope so that a risk is eliminated is called…‘Avoid the risk’. Lowering the probability is called…‘Mitigate the Risk’.”

“What about if we lower the severity of a risk, Da? What’s that called?”

“Either way, it lowers that total risk number so we should call it ‘Mitigate the Risk’.”

“Are they the only two strategies tha can use to deal with risks?”

“Let’s think about some of our other projects. What other things did we do when we were confronted with problems. Could there be other strategies?”

“In Caernarfon, there was that crazy prince, Arthog, who was holding up the project,” said Bleddyn. “You dealt with him but that was dangerous. What if you’d paid someone else to deal with him. What would you call that strategy?”

“That’s not removing part of the project to eliminate the risk. It’s more like giving part of the project to someone else to deal with and making them live with the risk as well. You’re transferring the risk to someone else. You’d have to pay them of course.”

“Aye, but tha wouldn’t have to tell them about th’risk added to that part of th’project would tha? Tha could just say, ‘I’ll give tha ten silver to get th’site ready for us.’”

“No. I don’t think that properly transfers the risk. When they realize they’ve been tricked, they will most likely give us our money back and say, ‘It’s yours again.’ No. You have to tell them about the risk so they can do the job properly.”

“But, Da. Why would anyone take that job and why would they do it any better than you?”

“I suppose it’s like when we hire specialists to do certain jobs. We hire quarrymen to cut rock for us because they do it better and cheaper than if we just dug around in the woods for rock. We could have hired an armored knight to bring in Arthog. He would have been safe and done it a lot quicker than our muddled efforts. It would have cost money but saved time.”

Fred was writing in his Project Management Guide. “So we have three strategies, Avoid, Mitigate and Transfer. Any others?”

“The rest we’ll just have to accept. It will cost more time and money to try and avoid, mitigate or transfer them than it will cost if they occur. So we’ll accept them as part of the project.”

“So we don’t do anything? Just leave them there to bite us whenever they want?” asked Bleddyn.

“Remember, son, they’re the small risks. We already figured that out when we did the risk qualification. But you’re right. Knowing the risk is there means we could at least put together a plan for dealing with the low probability, medium impact ones so that we’re ready if they hit the project. We could figure out what to do if it hits and only do that if it does comes to pass.”

“What do tha call that?”

“A contingency plan. We won’t do it for all the risks we accept, just the few we’re concerned enough about that their impact will be bad on the project if they hit. Those with a low impact, let’s just let them do their worst.”

Bleddyn turned the parchment back over. “So if we have risks in the upper right quadrant and in the top part of the upper left quadrant and the right part of the lower right quadrant, we must deal with them using the strategies of Avoid, Mitigate or Transfer. If they are lower probability but medium severity, those in the lower part of the upper left quadrant, we make contingency plans. All the rest of the risks, we accept, right?”

“That’s grand, Bleddyn,” said Fred. “I’ll add that graph and table to my guide.”

“Well fellows,” said Gwilym, standing and stretching. “I’m tired. What do you say we get some sleep? We’ll be planning all day tomorrow plus identifying lots of risks.”

The other two agreed and made preparations for sleep. Madoc was whimpering a little in his sleep so Bleddyn lay beside him to provide a little comfort. Fred stayed up by the firelight a little longer, writing the essence of tonight’s discussion in his guide before turning in.